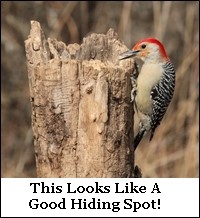

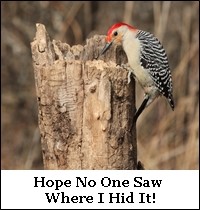

Here in Michigan we know as temperatures cool and the change of season is upon us, birds in your garden are looking for secret hiding places for their winter foods.

Many wild bird species store food for winter as a precaution against potentially meager food supplies in the colder months. This activity is called caching, and it typically takes place in the late summer and fall months when food is abundant. If you have trees full of nature’s bounty of acorns or a birdfeeder filled with seeds, you can witness firsthand the numerous quick trips being made by your garden birds between those food sources and a secret hiding place.

Bird species that frequently cache foods include jays, chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and crows. These birds store hundreds of seeds a day, and each seed is placed in a different location. With some birds using hundreds of caches, a large memory is required to relocate the seeds. It has been proven that in some species, the chickadees and titmice in particular, the birds use a physiological response to the need for memory: their brains grow larger! The portion of the brain that is responsible for memory is called the hippocampus and it increases in size in these bird species during the autumn and winter. When spring arrives, it shrinks smaller again in response to the newly emerging insects that provide a bountiful food source.

What about the non-migratory birds in your yard that do not grow a larger memory brain section? What do these wild birds do in the winter? Researchers hypothesize that these birds simply relocate the stored food. By providing an easily accessible food source, you can help your birds with their caching needs. You can also have a great time watching birds locate secret hiding places and discovering them throughout your yard.

The location of caches (hiding places) will vary depending on the bird’s habitat. Popular storage areas include seeds and nuts wedged into the bark of trees or beneath house eaves or shingles, and many birds will cache food by burying it or covering it with leaves or mulch, or pushing the food into soft soil. Birds have been observed pushing seeds into flower petals in an effort to hide them. In forested areas, birds are often responsible for helping tree growth from their stored nuts and seeds.

Chickadees cache more frequently during the middle of the day and will carry seeds (in the shell and out) and nuts, typically within 100 feet from feeders. Chickadees also cache insects and other invertebrate prey. Some of their favorite places to cache is in knotholes, bark crevices, under shingles, in the ground and on the underside of small branches.

Nuthatches prefer to cache hulled sunflower seeds, because they are easier and faster to cache and occasionally they will cache mealworms. Nuthatches generally choose heavier seeds because they are larger and have a higher oil content, caching within about 45 feet from feeders. Different from Chickadees, the Nuthatches are most active with caching early in the day, storing food in bark crevices on large tree trunks and on the underside of branches.

Tufted Titmice cache sunflower, peanuts and safflower, typically cached about 130 feet from feeders. Titmice cache one seed at a time and typically choose the largest seeds available, often removing seeds from their shell (80% of the time) before hiding them.

Insects are also looking for secret hiding places during the winter to avoid being found by predators – specifically the birds in our yards. Insect hiding locations include under the leaves of trees, under leaf litter, mulch, rocks and logs, in bark crevices and behind loose tree bark, as well as in, under and around rotting logs or dead branches of trees and bushes, inside seed heads of flowers, inside of woodpecker holes and within bird nests, and in openings in cement, mortar and bricks.

Insects can also create galls, which are orb-like formations in plants. They burrow into the plant and suck the inner plant tissue, causing the tissue to swell and form a sort of bubble. They sequester themselves inside the bubble, and the bubble of plant tissue protects them from the elements during the winter. These galls are no match for the Downy Woodpeckers in our yards. Their light weight allows them to cling onto stems without breaking the plant, and their strong bill taps a perfect hole for their barbed tongue to enter, extracting the insect from the gall with precision.

Autumn is a great time to sit back and take a moment to look for those secret hiding places and marvel at the wonders that happen in your own garden. Enjoy your birds!

Rosann Kovalcik,

Wild Birds Unlimited, Grosse Pointe Woods

*Red-bellied Woodpecker Images provided by Janet Kissick Hug

Have you joined our email list? Click here to sign up, it’s free and gives you access to sales, coupons, nature news, events, and more!